On March 5th, the Craeft project organised a distinguished panel of experts to review and provide feedback on the so far project’s achievements. The meeting featured the Craeft consortium members as well as the Craeft Advisory Board consisting of:

- Elisa Guidi from Artex orgnanisation, one of the partners of the Tracks4Crafts project and a former president of the WCCE

- Ignasi Guardans, a Co-founder and Chairman of CUMEDIAE aisbl, with a diverse career in law, politics, and cultural management, including roles in the European Parliament

- Representatives from the HEPHAESTUS project, Elena Raviola and Francesca Leonardi

- Daniel Carpenter, the Executive Director of Heritage Crafts, with a background in managing arts and crafts projects at Voluntary Arts, steering research on endangered crafts, and a initiator of the Red List of Endangered Crafts UK

and Craeft representatives:

- Xenophon Zabulis, a research engineer and project leader from FORTH

- Madina Benvenuti, crafts expert from Mad’in Europe

- Arnaud Dubois, an anthropologist from Cnam

- Sotiris Manitsaris, a research engineer at ARMINES

The discussions were lively and insightful, focusing on the project’s ethnographic protocol and the integration of digital tools across crafts.

The Craeft Ethnographic Protocol

Arnaud Dubois, an anthropologist, from Cnam and Sotiris Manitsaris, a research engineer at ARMINES, presented the initial outcomes of the Craeft project, highlighting the unique Craeft Ethnographic Protocol. Craeft methodological approach employs a rich blend of methodologies to understand the intricate connections between crafts professionals’ gestures, their tools, and their materials. The approach is rooted in three primary frameworks – Anthropology of Techniques, Sociology of Work and Ethnomethodology.

By combining these methods, we gather a comprehensive set of data: functional and structural from anthropology, individual and professional from sociology, and verbal and emotional from ethnomethodology. This holistic approach enables us to contextualise each piece of data within its cultural and symbolic framework.

This protocol positions craft practitioners as key decision-makers, allowing them to choose which gestures and techniques to record. The data collected includes detailed instances of craft practices, revealing intriguing insights such as the challenges of learning wool dyeing in Aubusson due to the scarcity of experienced practitioners.

What sets Craeft apart is our thorough capture of motion and context. Using a variety of sensors and tools, including cameras, wearables, and microphones, we not only track movements but also capture the surrounding scene and material interactions. This detailed data collection is enhanced by an egocentric vision technique, where craftsmen analyse and comment on their recorded gestures, uncovering hidden dimensions of their work.

Our goal is to explore correlations between different crafts, examining whether tools and techniques from one craft apply to another. This innovative blend of anthropological and engineering perspectives offers deep insights and fosters a better understanding of craftsmanship in a digital age.

One of the most discussed aspects of the Craeft Ethnographic Protocol was the use of egocentric recording followed by the video elicitation. By recording crafts professionals’ gestures and movements, crafts professionals can verbalise their cognitive knowledge and reflect on their embodied practices. This process allows for the discovery of hidden dimensions of their work, much like dancers use mirrors to perfect their movements. Elena Raviola noted the “cyber mode” of crafts professionals wearing helmets with cameras, sparking curiosity about their comfort and acceptance of this technology.

Madina Benvenuti shared her surprise at how positively the crafts professionals reacted to seeing their own hands in action, leading to moments of self-discovery and recognition of their own mistakes. This reflective process was seen as beneficial, much like how dancers refine their performances by watching themselves.

Sotiris Manitsaris also provided insights into the practical experiences of craftspeople using the new technology, noting their intrigue and collaborative spirit. Craftsmen were often surprised by their own unconscious movements, discovering new aspects of their techniques through the process.

Integrating Technology in Crafts: A Delicate Dance Between Tradition and Innovation

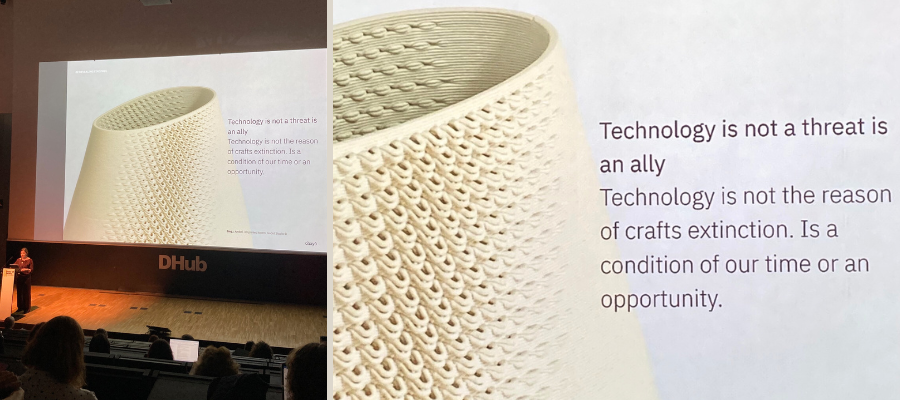

The concept of digital twins, brought into the discussion by Ignasi Guardans, involves creating a virtual replica of an object to test and modify before working on the real thing. Imagine having a digital double of a complex machine, allowing engineers to tweak and perfect it in a virtual environment before even touching the actual device. This approach minimises errors, saves time, and optimises efficiency.

Then he expanded the conversation mentioning 3D printing. This technology goes beyond mere simulation; it allows for the actual creation of objects layer by layer. Think about the possibilities: from manufacturing specific tools to creating intricate components that were once impossible to make by hand. 3D printing brings a tangible, practical aspect to the digital world, bridging the gap between virtual design and physical reality.

To spark the discussion he sets the question – how do these innovations affect traditional crafts? Here is where things get interesting. On one hand, using advanced technologies like digital twins and 3D printing to study and enhance craftsmanship is a fascinating research endeavour, but on the other hand introducing new technologies into traditional crafts could potentially alter them, pushing them towards becoming small-scale industries.

To answer this provocative question, Xenophon Zabulis points out the following example. Think about the introduction of electricity into pottery and glassblowing. Today, electric furnaces are standard, and we still consider these crafts traditional. We no longer need to use our feet to turn the pottery wheel or burn coal to heat the glass. Crafts have continually evolved, yet their essence remains intact. The balance is both delicate and subtle, which is why we emphasize using these technologies for training purposes. While there are robots that can carve wood and metal, our focus is on supporting the learning process and preserving the continuity of these handcrafts. By carefully integrating new technologies, we can enhance the training and practice of traditional crafts without losing their core essence.

Watch the full conference here

In summary, embracing digital twins and 3D printing in craftsmanship or any kind of technology is about finding the right balance between tradition and innovation, ensuring that while we adopt new methods, we also preserve the heart and soul of these timeless practices.

Policy and Protection for European Crafts

Craftsmanship is a living, evolving practice, and how it is influenced by policy is always a topic for discussion, this time brought to the conversation by Madina Benvenuti. Ignasi Guardans sparked a conversation about how the European Commission could protect European crafts through trademarks, like a “Made in Europe” label, or through specific legislations. He proposed measures like certified educational schools and geographical indications (GIs) to prevent imitations from non-European imports. He also suggested a label akin to the ECO label to distinguish between industrial and handcrafted products, raising questions about what truly constitutes a craft versus an industrial product.

Elena Raviola brought up an essential point: policies often aim to protect crafts but can inadvertently “freeze” them. Many craft makers feel that origin protections or limitations on manual versus automated work do not add value to their craft. Crafts are dynamic and change over time; rigid policies might sterilise them, turning vibrant practices into static museum pieces. Policymakers tend to believe that implementing these policies solves the problem, but the reality for craft makers is more complex.

Arnaud Dubois added to this by discussing the new Geographical Indication (GI) application process that is currently being filled at the Aubusson Tapestry. While these indications aim to protect and recognise the uniqueness of crafts, they also involve significant paperwork. Craftspeople find the administrative burden time-consuming and frustrating. They appreciate the protection but dislike the daily effort required to maintain it. Simplifying this process could make it more accessible and less burdensome for craftspeople.

Xenophon Zabulis highlighted how technology could help reduce production costs, increase income, and offer new ways to present crafts. For example, jewellers could benefit from technologies that allow them to showcase their work at exhibitions without the risk of theft. While some sectors already incorporate technology in production, many craftspeople primarily use it for marketing. Learning to use new tools for presentation and storytelling could enhance their visibility and appeal.

Ignasi Guardans concluded by noting the importance of setting clear standards for what constitutes a craft. Similar to bio or organic certifications, a “craft” label could distinguish true handcrafted items from industrial products. However, Madina Benvenuti cautioned against over-regulating by tying certification too tightly to the individual craftsperson, as this could stifle creativity and innovation.

Conclusion

The Craeft Expert Committee Meeting was a significant milestone in the project’s journey, bringing together an impressive array of experts to discuss the future of crafts. The insightful presentations and lively discussions underscored the importance of preserving traditional crafts while embracing innovative technologies.

The meeting reinforced Craeft’s commitment to enhancing the training and practice of traditional crafts through thoughtful integration of new technologies and recommendations. By fostering a collaborative and reflective environment, Craeft aims to preserve the essence of craftsmanship while preparing it for the future.